Whether sweeping the floor or posting on Instagram, our work can be one with our Zen practice

In the Zen tradition, work practice has long been part of the daily monastic schedule, dating back more than 1,000 years. Traditionally, it involved manual work, such as cooking, cleaning, gardening, and other routine activities that require minimal thinking. In a practical sense, work practice enables a monastery or residential training center like ours to function daily. But, more importantly, it’s a form of active zazen, bringing our practice “off the mat” and into the world.

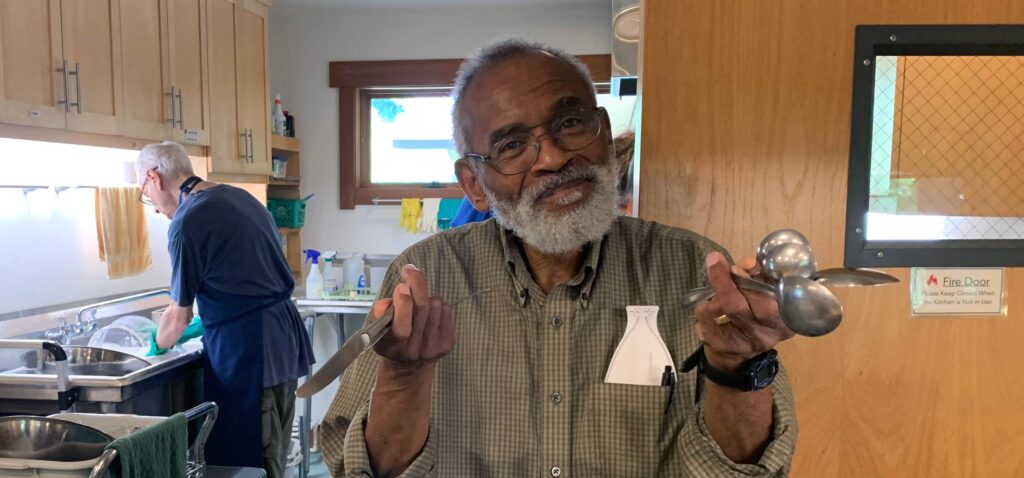

The work period is traditionally held after the morning sitting, following breakfast. Everyone is assigned a job; everyone contributes—in the spirit of the old Zen saying, “A day without work is a day without food.” At our center, on a typical day, work practice involves tasks such as preparing lunch, cleaning the zendo, and doing various chores that maintain the buildings and grounds. Often, residents are joined by volunteers, who take advantage of the opportunity to enrich their practice with the mutual support of Sangha. We all do our part in supporting a training program environment that is ideal for mindful work, including maintaining silence as much as possible.

However, what constitutes work practice has evolved over time to reflect the changes in the way humans live and work. Beyond simple manual tasks, today’s work practice includes preparing reports and spreadsheets, coordinating events, maintaining a website, creating social media posts, and troubleshooting an array of technology issues that can arise in offering hybrid sittings and sesshin. Each of these tasks requires a specialized skill set and use of the intellect to some degree or another, and they are necessary in order for our center to function and thrive in the 21st century. Likewise, many people in our Sangha perform intellectual tasks as part of their livelihood.

In contrast to simple manual work, engaging our practice can be more challenging when employing our thinking, analyzing, conceptualizing mind. The simplicity of just cleaning a toilet or just washing a bowl makes it easier to put our whole body-mind into what we’re doing. Yet, we can still experience a state of flow—that is, concentrated absorption—when performing cognitive work. It just has a different quality to it.

Work Practice Is Not About Goals, Efficiency, or Perfection

No matter the task or project that we’re working on, our attention should be on becoming completely one with whatever we’re doing, moment by moment. In this regard, work practice is not about goal completion. It’s not about getting from point A to point B. We’re so conditioned to set goals, and upon completing them successfully, we may be inclined to bask in a sense of accomplishment. But the spirit of work practice is just the pure doing without striving for some kind of attainment or end result.

Work practice is also not about efficiency; it’s not about getting something done in the shortest amount of time. This really runs counter to mainstream work culture where great value is placed on efficiency—especially from the vantage point of managers and CEOs, or those who are tracking “the bottom line.” At the same time, work practice is not about performing a task extra slowly or painstakingly. In some situations, we do need to respond swiftly; we need to keep to a strict timetable. What’s most important is that we’re being responsive to what needs to be done and that we’re absorbing ourselves fully in what we’re doing, again moment by moment.

Another point to embrace is that work practice is not about achieving perfection. Perfectionism is a personality trait that involves a preoccupation with some imagined standard of success. In other words, it’s an expression of wanting to be in control. Of course, doing an excellent job isn’t inherently bad. It can be a product of devoted attention and care—even love. But if our efforts are driven by an attachment to success or a fear of failure, then we’re caught up in thoughts and judgments about ourselves. We’re also clinging to ideas about how others may evaluate our work. Confronting habits of mind is part of the process of work practice, just as it is in sitting meditation.

Zazen In Motion

Put simply, work practice is zazen in motion, just like kinhin and chanting. But it’s certainly not a substitute for sitting. The stabilized mind of awareness that we hone while sitting is the foundation for practice in activity. It’s what equips us to be present, to unify mind and body.

Ordinarily, when our attention is divided, our experience of work is that of drudgery. We get bored, we feel impatient or resentful. We just want to “get it over with.” Even when doing a simple task such as raking leaves, if our attention wanders, we’re cutting ourselves off from the present moment. Perhaps we’re making plans or ruminating on something that happened in the past. We might feel frustrated by the volume of leaves or the weather conditions at the time. But there’s another way to rake, and that is no-mindedly. Just moving the rake back and forth, changing directions, and forming a pile. Just the musty odor of decaying leaves, the crunch of dried-up leaves underfoot, the crisp autumn air. Just that.

If you’re working on a koan or breath practice, in many situations it can be difficult, if not impossible, to keep your focus on it during work. It doesn’t make sense to be counting inhalations and exhalations while you’re chopping up carrots with a sharp knife. Not only will your attention be divided, but you risk injuring yourself. Sometimes we just need to let go of our particular practice in such moments or let it fade into the background. What is more important is that we direct our attention fully to what we’re doing, while letting go of random thoughts that pass through the mind.

Physical Work

When it comes to physical work, a wonderful resource is the book Sweeping Changes: Discovering the Joy of Zen in Everyday Tasks by Gary Thorpe. In a chapter titled “The Way of the Broom,” Thorpe says:

Could anything be simpler than sweeping your own floor? Complications arise only when “thinking” interferes with performance. When you become too conscious of your actions, too careful, you can encounter a kind of “nervous” negative energy. Oddly enough, too much thought can result in the same kind of disjuncture as absent-mindedness and lack of concentration. When you strain too hard to create beautiful music, you fumble the notes and the music suffers. Even sweeping the floor can become awkward and ineffectual if done with too much care.

We need to allow ourselves to flow unimpeded by thoughts. That said, when we’re learning a new task, we do tend to overthink it. Initially, we try hard to follow the instructions carefully, but when we get it into our body we’re off and running. It’s just like learning how to ride a bike. If we’re self-consciously thinking about using our feet to push the pedals and our hands to steer and operate the gears, we’re not going to enjoy the ride and we just might topple over.

We can experience joy in anything we do, including in what we may think of as rather mundane tasks, when we allow the self to drop away. When you work no-mindedly, there is the potential to be so absorbed that you’re not aware of what is happening around you. But that’s not the whole of work practice; there is also a mindfulness dimension of being aware of your body in space, harmonizing and working in concert with everything and everyone around you. In a practical sense, if we’re not aware of people and objects around us, nor of changing conditions while we’re working, we’re likely to bump into things, lose our footing, and perhaps even injure ourselves.

But What About Work that Requires Mental Activity?

Do we have to abandon Zen practice altogether? When you’re writing, reading, coding, or analyzing, it certainly can feel like thought-centric work, especially if you’re sitting for hours at a desk, staring at a screen. But there are things you can do to engage your practice even with these kinds of work—first and foremost by simply focusing on what you’re doing and letting go of extraneous thoughts just as one would with manual work.

When I was a university professor, I used to spend a lot of time working at a computer, reading and writing, and to a lesser degree I still do as a Zen teacher. In order to get intellectual work more into my body and out of my head, I learned that it helps to pay attention to posture while seated at my desk. It also minimizes the potential for issues with back or hip pain due to poor posture. Taking advantage of screen breaks is also helpful. Every time you take a break, whether it’s to stand up and stretch, or to go use the bathroom or get a drink of water, it’s an opportunity to reengage your practice in a bodily way. This requires us to drop the cognitive work, drop it right there in that moment when we make the shift to taking a break. Whatever you were just thinking about at your desk, drop it and be one with what you’re doing right now. Just opening the office door, just walking down the hall. It’s an opportunity to be one with your body in motion, whereas at your desk you may be largely stationary with the exception of fingers tapping at the keyboard.

It is also beneficial to avoid juggling multiple tasks at once, a habit that sabotages immersing ourselves in what we’re doing. If we’re toggling back and forth between, say, preparing some written report and checking our email or cell phone, our attention is split. The same goes with listening to music while working. In a Hidden Brain podcast about the value of “deep work,” Cal Newport, author of Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World, says that while most people know that there’s a price to pay for multitasking, “What they’re still doing is every 5 or 10 minutes, a ‘just-check.’ Let me just do a ‘just-check’ to my inbox. Let me just do a ‘just-check’ to my phone real quick and then back to my work. And it feels like single-tasking. It feels like you’re predominantly working on one thing. But even those very brief checks, that switch of your context even briefly, can have this massive negative impact on your cognitive performance. It’s the switch itself that hurts, not how long you actually switch.”

Newport is describing the difference between doing one task at a time and doing it simultaneously with the awareness in the back of your mind that you’ve got emails in your inbox or a text message waiting for you. While Newport’s research focuses on the impact for work performance, we can readily see that it also applies to Zen practice.

The way to protect your mind from such distractions is by consolidating tasks or designating time for “shallow work,” says Newport. For example, checking email only once or twice a day and putting your phone on DND—even better, putting it somewhere out of sight. Another strategy is to designate blocks of time to work without interruption. The extent to which one has the opportunity to do this will depend on one’s office environment. In some work circumstances, we need to make ourselves accessible and available to others.

True Nature

The most important takeaway on work practice is that cognitive tasks need not be construed as activities that are separate from or unconducive to Zen practice. We don’t abandon our True Nature when we’re using our thinking mind. It’s not other than who we are, even when we misuse our attention. Our True Nature is always and already functioning whether we realize it or not.

The famous lay practitioner Layman Pang (740–808), who made a living and supported his family as a merchant, said, “Drawing water and carrying firewood are spiritual powers and sublime functions.” So it is with writing reports, adding up numbers, and tending to a customer. In truth, there’s nothing about our lives that is not practice. Nothing. No event, no location, no time of day, no activity, no single moment that is not the embodiment of our True Nature. / / /

Zen Practice and Computing

A summary of the suggestions above

- Pay attention to your posture.

- Take screen breaks, immediately dropping cognitive work, re-engaging your practice in a bodily way.

- Do one task at a time. No multi-tasking (not even quick “just-checking”). Immerse yourself in what you’re doing.

- Designate a time for “shallow work.”

- Put your phone away or in “Do Not Disturb” mode.

For those interested in deepening work practice in a supportive environment, you might consider trying Residential Zen Training at the Center for a few weeks or longer.