Learning to find a “good seat” for meditation may take some time and experimentation. Whether you sit in a chair or in the (increasingly rare) full lotus position, three basic principles to bear in mind are:

- Stability

- Alignment

- Relaxation

Stability. In order to settle the mind, it’s important to settle the body. If your body is balanced with a low center of gravity, the natural result is stillness. In a chair, stability means sitting up straight, perhaps on the edge of the chair, and making sure your feet are both flat on the floor or a cushion, if you have shorter legs. On a sitting cushion, stability means aiming for a tripod effect, with your pelvic “sit bones” and your two knees forming the three points of contact.

Alignment. Sitting up straight, with the head and shoulders aligned properly with the pelvis, is especially difficult for those of us who are habitually hunched over tablets and phones. The best way to make sure you are sitting in good alignment is to ask one of the zendo monitors to check your posture, either before or during a sitting. (And don’t be surprised if a monitor, unasked, adjusts your posture during a sitting.)

Relaxation. Most Zen students are initially somewhat tense while sitting. The unusual posture, unfamiliar surroundings and rituals, the presence of other sitters, physical pain, and most of all, tormenting thoughts, can all contribute to tension. When you notice that you are tensing up, you can get relief quickly by relaxing into the pain, exhaling and moving your attention down into your hara (a few inches below your navel). Pushing pain away only makes it worse: resistance breeds more tension, not less.

A special note about your eyes: in Zen meditation, the eyes are kept open. Allowing the light in helps promote alertness, and also makes your sitting meditation more like your everyday life. Once you’re in a comfortable seated posture, lower your gaze, look at the floor four or five feet in front of you, and then let your eyes go slightly out of focus so they are relaxed.

Sitting Postures

These descriptions were written by the Center’s late founder, Roshi Philip Kapleau, in his classic, The Three Pillars of Zen, which, in 1965, was the first book to explain Zen meditation to a Western audience. Contemporary comments are added in italics.

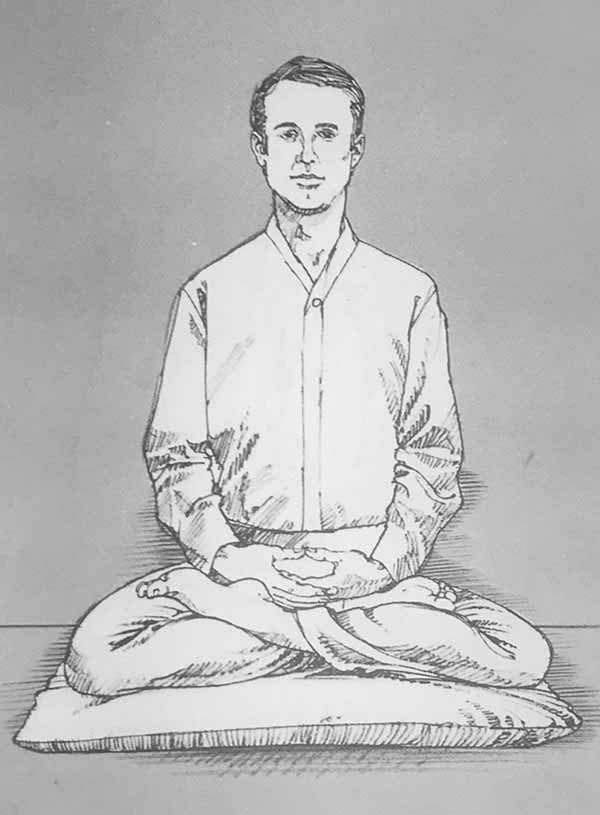

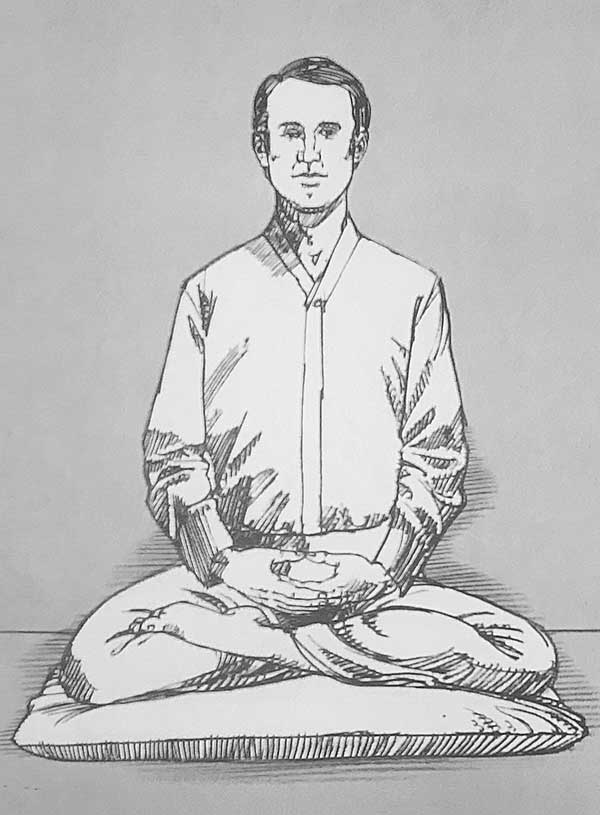

Note how the arms and the legs all come together, centering the body in the abdomen.

The round cushion shown, called a zafu in Japan, is stuffed with kapok or another firm filling. The floor is covered with a mat, which cushions the knees. A folded blanket or yoga mat could be used for the same purpose.

This posture may be reversed, with the right foot on top, when the left knee or ankle gets tired.

This posture may be reversed, with the right foot on top, when the left knee or ankle gets tired.

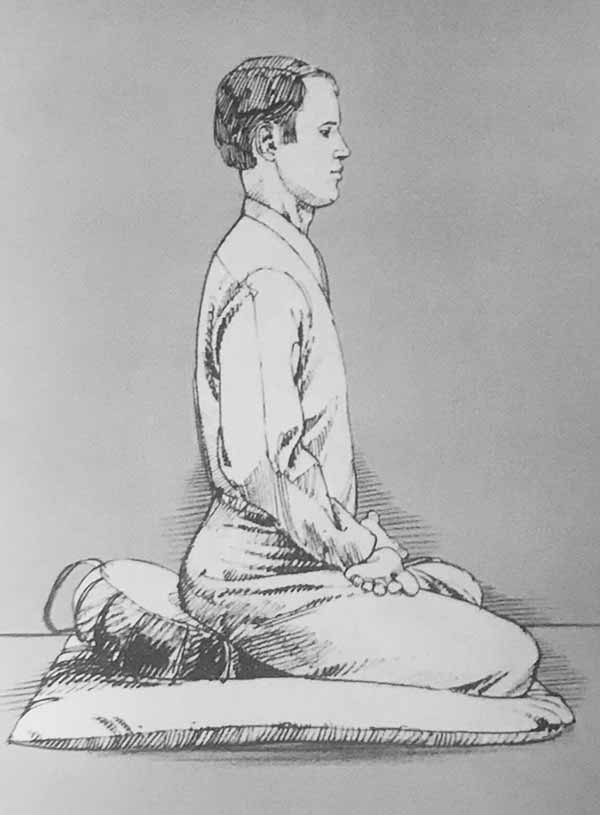

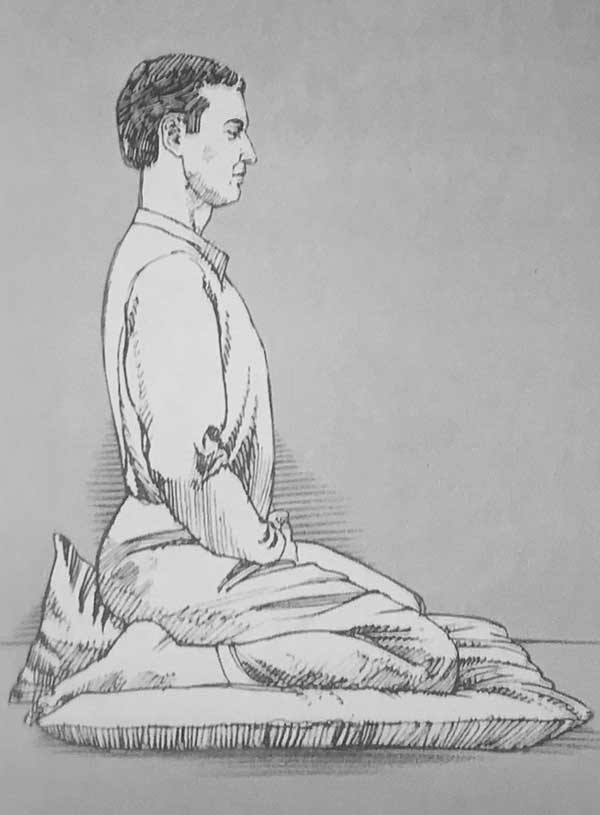

Fig. 5. The so-called Burmese posture, with the legs uncrossed, the left or right foot in front and both knees touching mat. Here, too, a higher sitting base may be necessary so that both knees rest squarely on the mat.

Fig. 5. The so-called Burmese posture, with the legs uncrossed, the left or right foot in front and both knees touching mat. Here, too, a higher sitting base may be necessary so that both knees rest squarely on the mat.

Another option for the Japanese position is to use a round cushion, either flat or on its edge.

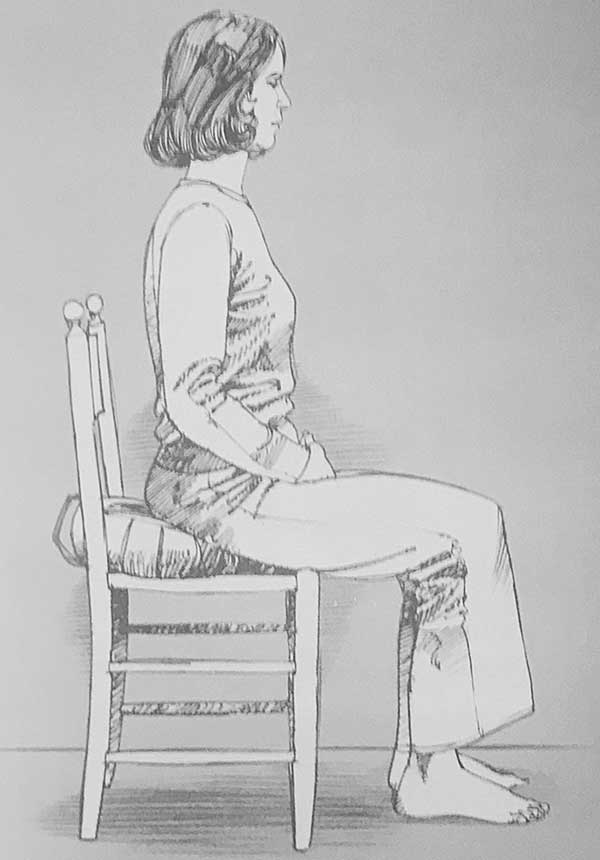

Note that the sitter maintains an upright posture and does not lean back in the chair. People with shorter legs may wish to have a yoga block or firm cushion under their feet.

Breath Meditation

Most Zen practitioners begin with a breath-counting practice. Once you are stable and relaxed in your sitting posture, your eyes are lowered, and you can feel your center of gravity sinking into your abdomen, begin the count. Count “one” on your inhalation, “two” on your exhalation, “three” on your inhalation, and so forth up to the count of ten. At that point, begin again at “one.”

If your thoughts multiply and you lose count, take heart: you are human. Simply let go of the thoughts and begin again at “one.” If you find yourself counting “fifteen”…”sixteen”…simply return to “one.” Don’t get derailed by beating yourself up or evaluating your practice in any way. In fact, the very act of bringing yourself back to the count is at the heart of Zen. By doing this over and over, you are building up your “mind muscle” – the habit of returning to the present moment – which will enrich your life immeasurably.

When to Sit

The most fruitful time for people to sit is usually in the morning. You probably have more energy at that time of day, and sitting helps set the tone for your entire day. However, the best answer to this question is “every day.” Whenever you can make it work, depending on your schedule, is the right time to sit. Even if you can only spare five minutes a day, it is more important to be consistent on a day-to-day basis than to sit for hours at a time but only sporadically. In this way, zazen becomes not just a “special practice” but an integral part of your day-to-day life.

Illustrations by Richard Wehrman.