“Both painting and sitting require a willingness to stay in one place for hours.” An interview with Dave Dorsey.

by Dave Dorsey

Zen Bow: How long have you been a member of the Rochester Zen Center?

Dave Dorsey: I’m getting too old to remember the exact year I joined in the 90s. Actually, my first encounter with the Center was in college, when I was a student at the University of Rochester and came to my first workshop, run by Roshi Kapleau, in the early 70s. I began sitting then, and have been doing it off and on ever since. After I joined I spent some regular time in the morning at the center, but I’ve drifted into simply sitting at home. It’s been quite a while since I’ve visited, but I’m proud to be a member. My one weekend sesshin at Chapin Mill as it was still being built, I think, was the most effective time I’ve spent on a cushion.

ZB: Were you sitting before you joined, or did you learn to sit at the RZC?

DD: I didn’t have any kind of meditation practice before that first workshop in the 70s.

ZB: What was your turning point? Why did you decide to take up Zen meditation?

DD: I came out of high school with a sense of burning philosophical doubt: a kind of tenacious questioning about meaning that seemed urgent but unanswerable. The nature of this doubt is hard to describe without muddling it up, but it was difficult and life-changing. After contending with this state of unrest for a couple years, as a freshman at the University of Rochester I finally got around to reading J.D. Salinger’s Glass family stories, which introduced me to a variety of spiritual traditions: Vedanta, Zen, Russian Orthodox Christianity. His fiction offered me references to a variety of spiritual paths.

I was so impressed by Salinger that I made out a reading list of Salinger’s favorite authors and read them, one after another, as if he had introduced me personally to each of the writers themselves and said, “You two should get to know each other.” Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Proust, Henry James, Keats, Coleridge, and so on—some of whom I’ve been rereading lately after all this time. As a result, I spent the summer after my freshman year at U.R. reading all of Proust and most of Kierkegaard. Kierkegaard was crucial: my parents were Presbyterian and I still consider myself a Christian, but a few of his insights were very close to the paradoxes one faces in Zen practice when trying to break through how the mind entraps itself without realizing it. In addition, I made a list of references to spiritual disciplines and other writers mentioned in Franny and Zooey: Ramakrishna, Meister Eckhart, the Upanishads, the haiku translations of R.H. Blyth and D.T. Suzuki. That last name was the door to my interest in Zen. One thing led to another. In the middle of all this self-directed study, I was delighted to discover a new organization devoted to Buddhist meditation here where I lived. I signed up at Arnold Park and that’s what got me started.

ZB: Tell us a little about your career trajectory, and when/why you started to paint?

DD: I began painting as an outgrowth of playing a Fender guitar in a couple of garage bands in high school. I wanted some large posters of Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton to put on my bedroom wall, but didn’t know where to find them—this was long before the Internet. During a brief illness, out of boredom, I found a starter set of oil paints my father had used once to make little Cubist-type scenes on Masonite he hung on our walls. I used them to copy the portrait of Mike Bloomfield by Norman Rockwell on the cover of “The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper.” I still have that oil painting on paper—I discovered it a few weeks ago in the basement.

I went from that to a 4′ x 4′ copy of the cover of Band of Gypsies which I bolted to my wall—it was painted on soft thick fiberboard. When I discovered an Art News Annual with a long feature about Van Gogh, my interest in painting began to take the place of my desire to play the guitar. And I’ve painted ever since, even while making a living as a writer. I chose to study literature and writing rather than painting because I didn’t entirely trust what was happening in the art world at the time and still feel wary about much of what goes on there—I wanted to keep my distance from it and yet still be an artist.

ZB: How do you think your Zen practice informs/interacts with/inspires your painting?

DD: I’m still a beginner at Zen, and I often feel that way as a painter when I stretch a new canvas. When I sit, I count my breaths. Even after decades of doing this, I mostly can’t do it consistently even over short periods of time. I have to keep coming back to the counting after losing track, as most people do. Occasionally (usually in my sitting with other RZC members) my mind has become entirely quiet, but this requires sustained effort. I know all of this is just the doorstep to serious Zen practice, which is why I consider myself a beginner. Yet I think even this kind of effort is central to my painting in a couple ways.

It was easier to talk about a connection to Zen back when I was doing abstract expressionist work, where the improvisational nature of the brushwork had much more in common with Japanese and Chinese painting inspired by Buddhist traditions. But what most painting, including my own, has in common with sitting is the need for sustained attention to the task at hand over long hours. Both require patience and an ability to ignore restlessness and distractions. And both not only require, but are entirely about, paying attention: it’s the central discipline of a representational painter and it’s also the primary effect of the finished painting on the viewer. The point is to see what’s there with fresh eyes. Both painting and sitting require a willingness to stay in one place for hours in ways that often feel unpleasantly constraining for the purpose of simply being intensely aware, period.

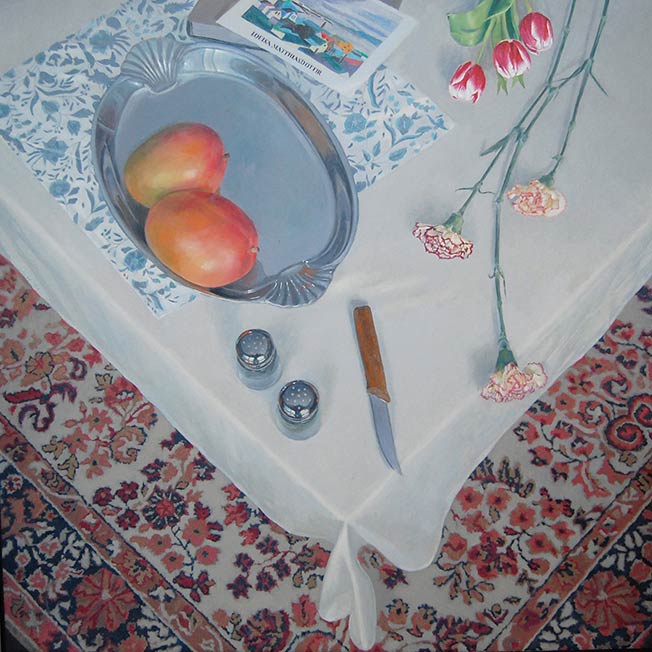

I paint mostly still lifes now, in various modes, and I think of it as a way of attending to the “is-ness” of the simplest, most commonplace things with care. It’s a way of becoming aware of the simple fact of something’s simply being there, disclosing itself to me in a certain way—the fact that something simply is—which gets so easily taken for granted and overlooked when daily human purposes come into play. It teaches me how difficult it is to actually see what’s there: the actual tones that exist in front of me rather than the ones I think are there from what I think I know about the object or scene. Painting requires a trained mindfulness that also makes it possible for the act of painting to invest an image with qualities that I’m not even conscious of, qualities that somehow arise on their own, while I’m busy thinking about getting something technical accomplished on the canvas.

ZB: A few years ago you borrowed a human skull from the RZC [used for the human realm in Great Jukai] to use for a painting. That seems very Zen-like. Now you are painting hyper-realistic candy jars. Say what? Can you tell us about that transition?

DD: My methods are photo-realistic, but the jars are more painterly and not as precise as most hyper-realism these days. The skulls I’ve done are actually more exact than the candy paintings. The three skulls I painted were almost the antithesis of the subjects I usually pick. My primary interest has always been color, and this is a difficult passion when you are painting most of what’s in the world accurately; most things aren’t that colorful. The skulls were the least colorful objects I’ve ever painted and a genuine detour for me. They were done on a dare, more or less, but I loved doing them. An artist I know suggested I try a skull so I tried three of them: the RZC’s human skull as well as baboon and cow skulls borrowed from an artist. I got to keep the cow skull.

Technically, in the Western painting tradition, they are “vanitas” paintings—time is short, use it well—but I loved them because of the complexity of light and shadow, the texture of the bone, all of the ways in which they could have passed for rock or driftwood. Painting a skull reminded me of painting a dahlia, actually, but it was even more challenging. Rendering the box that the RZC’s skull was stored in was actually the biggest challenge. It was worn, so the ribs in the cardboard created ridges in the surface of the box, and the old packing tape had yellowed a bit, and the words “actual human skull” were written in large script across the face of the box, which made me laugh. (Try to ship something with that sort of notice on the side now.) It looked impossible, a complicated mélange of textures and colors and shapes. Much like the skull itself. I don’t know how I painted that box so accurately, and I’m sure I couldn’t do it again quite as well.

When I started the painting, I thought it would defeat me but I ended up doing things I didn’t know that I could do. In a way, the box carried the same aura as the skull: old, battered, forgotten and pretty much discarded until I started paying attention to it for a bit. I surprised myself with that one.

The large candy jars, and jar paintings in general, I’ve been doing off and on for a decade, and they actually fulfill my core motivation to paint more effectively than anything else I do: they are a truce between representation and abstraction for me. The scale and the way the jars are brought up close to the viewer, so that they seem near the surface of the canvas, gives me a chance to make color the primary concern, within the geometric patterns formed by the contents of the jar. It’s as close to “pure painting” as I’ve gotten and is one way I’ve responded to my love for color field painting in the ’60s, even though a jar full of objects is also a still life of sorts.

ZB: What’s next?

DD: A series of paintings involving candy of a different sort. Without jars.

ZB: What didn’t I ask that I should have?

DD: I had a five-page essay with charts and graphs prepared in case you asked, “Does a dog have Buddha nature?” Maybe next time. / / /