Koan commentary: “Kempo’s One Road”

The Case

A monk once asked Master Kempo, “A sutra says, ‘The Bhagavats in the Ten Directions, one straight road to Nirvana.’ I wonder, where is that road?” Kempo lifted up his stick, drew a line in the air, and said, “Here!”

Later a monk asked Ummon about this. Ummon held up his fan and said, “This fan jumps up to Heaven and hits the nose of the King of the gods. The carp of the Eastern Sea makes one leap and it rains cats and dogs.”

The Commentary

One goes to the bottom of the deep sea and raises a cloud of sand and dust. The other goes to the top of a towering mountain and raises foaming waves that touch the sky. The one holds, the other lets go, and each, using only one hand, sustains the Dharma. It’s like two children who come running from opposite directions and crash into each other. In this world those who are truly awakened are difficult to find. But when seen with the true eye, neither of these two great teachers knows where the Nirvana road is.

The Verse

Before taking a step you have already arrived.

Before the tongue has moved, the teaching is finished.

Though each move is ahead of the next,

know there is still another way up.

Kempo is the Japanized name of this Chinese master, Yuezhou Qianfeng, who lived in the late eighth and early ninth centuries. In Zen’s Chinese Heritage, the mother lode of biographical information about the Tang Dynasty Zen masters, nothing is recorded about his life.

Ummon is the Japanized version of Chinese master Yunmen, who appears in more koans than anyone except Zhaozhou (Joshu). But we’ve so often heard about him in teisho that I’ll forgo telling his story again this time.

Koans are uniquely Zen in their use as a meditation device. Most koans that have come to us in these collections are dialogues between masters and monks. Sometimes, they’re stories. But they all have an element of paradox, or a contradictory quality, to them. If we engage the koan seriously, if we take it to heart and really bore into it, then because of its illogical nature it forces us out of the box of this rational mind of ours into the Incomprehensible.

In Zen Comments on the Mumonkan, the author, Shibayama-roshi, quotes his own teacher on the role of the koan in Zen: “[T]he koan does not lead a student along an easy and smooth shortcut…. [It] throws the student into a steep and rugged maze where he has no sense of direction at all. He is expected to overcome all the difficulties and find the way out himself.”

Shibayama’s teacher then compares the predicament of the koan with a blind person trudging along with his cane, with the koan “mercilessly” taking the cane away from him, turning him around, and pushing him down. The koan, then, strips us of our myopic way of relating to the world so that we may broaden our vision.

So: A monk once asked Master Kempo. “The sutra says….” He’s quoting the Surangama Sutra, one of those most highly regarded in the Zen school of Buddhism. Sutras are collections of the Buddha’s teaching, most of them purportedly in his own words. “Purportedly,” because his discourses weren’t written down until some two centuries after his death. Until then they were passed on orally, and supposedly verbatim, as memorized by Ananda, his attendant of twenty-five years. Since the sutras comprise many, many volumes, it strains credibility that the Buddha’s millions of words could have been accurately preserved for two hundred years. But we do know of people even today who have such stupendous memories. I’m thinking of reports in The Guinness Book of World Records of people — from India, as I remember — who have accurately recited hundreds of successive digits of pi in order. So, who knows?

But Zen has always been known as a teaching “without reliance on the sutras,” and “beyond words,” so the verbal accuracy of the sutras is not of concern to us. What matters in Zen is the spirit, or the meaning, behind the words—the moon itself, not the finger pointing to it.

Still, many of our most illustrious masters came to Zen only after years of formal sutra study. And the Surangama Sutra is one they probably would have studied. Other Mahayana sutras highly esteemed in the Zen school are the Lankavatara Sutra (reportedly Bodhidharma’s go-to text), the Lotus Sutra, and the Diamond Sutra. Also the Vimalakirti Sutra and the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch, though this last features the discourses of Hui Neng, not the Buddha. It was later designated a sutra in reverence for his teaching, which established the character of Zen as we know it today.

Again, from the Surangama Sutra: “The bhagavats in the ten directions, one straight road to Nirvana.” Bhagavat is a Hindu term, and I think this is the only koan in which it appears. There is a lot of overlap between Hindu teaching and that of Buddhism. Hindus say that Buddhism is an outgrowth of Hinduism—and even that the Buddha himself was a Hindu! One of the major differences between the two religions, though, is that the Buddha, having realized the intrinsically enlightened nature of all people, opened the gate of liberation to all equally, regardless of caste.

For the purpose of this koan bhagavats can just be understood as a general term for the enlightened ones, or buddhas. In the zendo we’re heralding them when we chant: “Ten directions, three worlds, all buddhas, bodhisattva-mahasattvas.” Throughout all space and time, all beings, enlightened ones: one straight road to Nirvana.

Nirvana is one of those Buddhist words, like karma, that has trickled into the English language. But this doesn’t mean that anyone really understands it. One literal translation of it is “extinction,” but from way back when the first Buddhist texts arrived in the West, people commonly have thought of Nirvana as the Buddhist heaven. Well, that’s not entirely a misunderstanding. It’s certainly not literally a place we go, but we can find our way there in sesshin. We can experience the essence of Nirvana in samadhi. And that is a heavenly experience.

“I wonder, where is that road?” He’s asking, “What is the Ultimate? What is the Way?” And then Kempo lifted up his stick, drew a line in the air, and said, “Here.”

Kempo could have said, “This. Just this. It’s all here. It’s all this.” In the deepest sense, there is no there, or then: it’s all here. And we discover this if we delve into this question or another fundamental one. If we go deep enough, we realize: Where else could it be but right here? This is the only thing that’s real.

Everything else is thoughts. Some other place? Well, we have words for that. Nevada, South Africa, the moon…. But where are those places right now? They’re just words. Where is Brazil, where is Russia? I don’t see them. What about the future? Where is that, except in our thoughts? And the past? Thoughts. We’re always looking, looking, looking, toward the future, or back into the past. Imagining something else, some other place, some other time. And so as a result, we miss just this. We miss HERE.

You may protest, “Wait—I remember the past. I even have objective reports of it, from the news and from books.” But memories and news and biographies themselves exist only in the present.

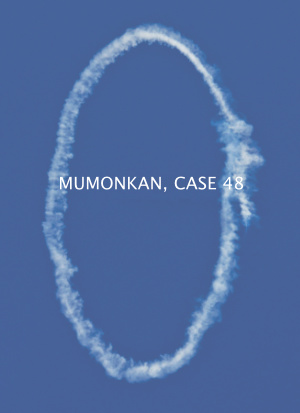

Another translation has Kempo drawing a circle instead of a line in the air. The circle is the one symbol used in Zen. It’s about as close as we can come to representing our formless Essential Nature in form. In the verse to case 23 in the Mumonkan, Zen master Mumon reminds us, “You describe it in vain, you picture it to no avail.” But we try anyway, wearing this True Self as the ring in our rakusu and painting it calligraphically as an enso. Want to picture this “True Self that is no-self,” as Hakuin puts it? Go look at the big, brush-stroked circle displayed at the end of the hallway outside the zendo. Take a look at who you really are. (Or stay in the zendo and do that!)

“Where is that road?” Now, Kempo’s response must not have satisfied the monk, or he didn’t get Kempo’s point. So then he went to the great Ummon and asked the same question: “The Sutra says, ‘the bhagavats in the ten directions, one straight road to Nirvana.’ Where is that road?” And Ummon gave a very different response from Kempo’s: He held up his fan and said, “This fan jumps up to heaven and hits the nose of the king of the gods. The carp of the Eastern Sea makes one leap and it rains cats and dogs.”

What in the world is he saying here? It is the job of a student working on this koan to demonstrate first the spirit of Kempo’s response, and then of Ummon’s response. The whole point of demonstrating is that we are then forced to embody our understanding, and the teaching embedded in the koan. It’s one thing to discuss Buddhist doctrine; it’s another thing to assimilate it, to incorporate it enough that we can present it in our bodies. To grasp this koan, one has to inhabit these two masters, body and mind.

To present one’s understanding of a koan, often you have to first determine the states of mind, and even the levels of understanding, of the protagonists. A Chinese master offers his own take on Kempo in this commentary: “Kempo’s medicine for a dead horse didn’t work as medicine. This monk was a man who had already perished and lost his life [meaning he had come to awakening]. Ummon gathered some reviving incense to enable the dead to come back to life again.”

And that’s the symmetry in this case; the two sides of our nature, the two sides of reality. And that’s what Mumon gets to in his commentary: “One goes to the bottom of the deep sea and raises a cloud of sand and dust. The other goes to the top of a towering mountain and raises foaming waves that touch the sky.” Which master is diving underwater and which is soaring? Or does it even matter? These two lines also can be taken together as a single point Mumon is making. What point is that?

“The one holds, the other lets go.” Holding and letting go constitute just one of countless pairs of opposites that were baked into the philosophy and religion of China since long before Bodhidharma was sitting there in his cave. Taoist philosophy is laced with these polarities, and there’s a lot of Taoism in Zen. The Sixth Ancestor, Hui Neng, in his instructions to his disciples enumerated some thirty-six such pairs, including activity and tranquility, the pure and the muddy, permanence and impermanence, advance and retreat, yin and yang of course, and as presented in this koan and every koan, form and formlessness, the phenomenal and the void.

To say that Zen is beyond words and concepts doesn’t mean we don’t make use of them. Like the sutras themselves, they articulate—make more conscious—the understanding we uncover through practice alone. We can appreciate these many sets of polarities as a way to better understand the range of differences that they highlight. In this way, Hui Neng says, “The interdependence and mutual involvement of the two extremes will bring to light the significance of the Mean.” “The Mean”—in other words, the Middle Way that is the Dharma.

Buddhist doctrine rests on the two-fold truth of emptiness and form. “Holding” is the emptiness side, that of non-differentiation, no-thingness, sunyata—the essence of everything. But there is no such world of just negation. It’s an abstraction. “Letting go” is the side of differentiation, of phenomena, of self-and-other, of “name and form.” These are just two perspectives, but the reality is not two.

With respect to the actual practice of Zen, “holding” could be seen as the highly structured, spare realm of formal sitting, where we are largely disengaged from the sense world, especially in sesshin. Silence. Eyes down. This is where we’re most likely to be able to see into the formless aspect of reality, through turning inward, detaching from objects.

It’s the other side that completes the work of Zen: bringing forth our practice into the realm of phenomena. Zen practice in activity, and out in the wide world, represents the “letting go.” Here we let go of our cushions and engage with life in its profusion of changing circumstances and conditions. Leaving the zendo, our practice now becomes socializing again, smelling the flowers as we walk outdoors, driving through traffic, returning to family life, to work, going to the supermarket. Yet this side, too, is just half of it. Nietzsche said, “It is good to express a matter in two ways simultaneously, so as to give it both a right foot and a left. Truth can stand on one leg, to be sure, but with two it can walk and get about.” People who think that it’s enough to “practice in activity,” without sitting regularly, are deceiving themselves. The quality of the active meditation is dependent on the sitting.

The world of thingness, of differentiation, is the only world that most people really know. But by itself it can’t be reality. The “nothing” side is obscure. Through our senses we perceive every thing—forms, phenomena, objects—but not “nothing.” Still, I would bet that everyone who undertakes Zen practice seriously—and that would mean everyone who goes to sesshin—has gotten some inkling of that other side: the silence in sound, the stillness in movement, the no-self in self. But to confirm the reality of that side through direct experience means dissolving our attachment to concepts. Zen master Linji, in his characteristically fierce way, exhorted his monks to seize the day, on the mat and off, to be done with the idea of “others” as apart from us:

Followers of the way, if you want insight into Dharma as is, just don’t be taken in by the deluded views of others. Whatever you encounter, either within or without, slay it at once. On meeting a buddha, slay the buddha. On meeting a patriarch, slay the patriarch. On meeting an arhat, slay the arhat. On meeting your parents, slay your parents. On meeting your kinsman, slay your kinsman. And you attain emancipation. By not cleaving to things, you freely pass through.

When we transcend thoughts and concepts, nothing obstructs us. “Nothing” stands brightly before us.

We can see the interplay of holding and letting go all around us. It forms a continuum of teaching styles, with the most demanding teachers at one end and the most allowing, or relaxed, at the other. Probably the most “holding” of all Zen teachers was the Chinese master who, whenever asked about the Dharma, would just silently turn his back on the questioner. In teaching, that’s the purest expression of the negation aspect, but it surely would have arisen out of faith in the questioner; he was withholding what he knew the student could discover on his own when forced back on his own resources.

At the other end of the teaching spectrum is the prominent teacher in Europe who would not require his students working on subsequent koans to spend more than one dokusan on a koan. If the student’s presentation missed the point, the teacher, rather than ring him out, would give the proper demonstration himself and assign the student her next koan. Since the effectiveness of teaching depends so much on the particular student and on timing and other circumstances, we can’t really pronounce any style as better or worse in the abstract. As always, it comes down to skillful means.

In academic teaching and in coaching and mentoring generally, we can see a similar range of styles between, on the one hand, those who are strict and exacting, and on the other those who are more allowing, encouraging, and willing to make exceptions. Likewise, parenting styles fall along a range of strictness and permissiveness, and fortunate is the child whose parents know when to say no and when to yield—“when to hold and when to fold.”

The same diversity of teaching styles would, by extension, apply to Zen centers and temples. There are centers that have more relaxed discipline and looser policies than others. A teacher, now deceased, who offered a Zen-like meditation outside Rochester allowed participants at her retreats to skip whatever sittings they wished; they never needed to show up. People generally land at centers whose style they feel an affinity with, but geographical proximity is another consideration.

Aside from Zen practice and teaching, there are other aspects of life we can see in terms of holding and letting go; for example, on the conservative-to-liberal spectrum, with social, economic, and institutional conservatives contrast-ing with liberals in those fields. Religious conservatives hold fast to scripture and tradition; political conservatives to a more literal reading of the Constitution. Among translators, too, there is a range between those who hold to a more literal rendering of the text and those who translate more freely in order to make the text more accessible. People also differentiate themselves as to which is more important: principles or pragmatism. Even in linguistics, purists holding to conventional grammar and diction face off against modernizers, adapters.

Letting go is the free-acting, the expressive, the expansive, the creative: arts, humor, comedy, the profusion of things. But that world itself can become hollow without insight into the other side, the no-thingness of things. Before discovering Zen, Roshi Kapleau was something of an art collector and an aficionado of classical music. But as time went on he grew weary of what he later described as “the joyless pursuit of pleasure.” Then his karma took him to the war crimes trials in Nuremberg and then Tokyo, where he strolled through the gardens of a Zen temple and was struck by lightning.

And each, using only one hand, sustains the Dharma. It could sound as though Kempo and Ummon are each presenting just half the truth. But, Mumon assures us, in their responses each “sustains the Dharma.” So both masters must be presenting the whole truth. In that case, where in Kempo’s spare response is the “letting go”? And where in Ummon’s exuberant response is the “holding”?

Both Kempo and Ummon would long since have seen the illusory nature of conceptual templates like holding and letting go. And neither of them would have saddled himself with the designation Mumon playfully gave him. In fact, the expansive response Ummon gives here is the opposite of the “one-word responses” he was famous for. And even though Ummon playfully answers the monk in colorful terms of cause and effect—“this begets that”—he’s free to do so because he’s realized the other side of causation: the Absolute. Or as Kempo put it, “Here!”

Another commentary, this from another Chinese master, comparing Kempo’s response with that of Ummon’s: “Kempo points out the road, indirectly helping beginners. Ummon then went through his transformation, so as to make people of later times be unwearied.” If we had only the side of holding, of sitting zazen, this could get wearisome. But it never has to be. We have to emerge from our sitting. We have to emerge from sesshin at some point. We have to eat, we have to talk, we have to work, we have to laugh and to love.

It’s like two children who come running from opposite directions and crash into each other. In this world, those who are truly awakened are difficult to find. But when seen with the true eye, neither of these two great teachers knows where the Nirvana road is. The terms holding and letting go, slaying and reviving, can be useful in describing function: Kempo’s and Ummon’s responses in this koan, and our own range of responses to circumstances in our lives. But then there is just the nature of things—their being, our being—and the two aspects of that realm are better described in abstract terms: the relative and the Absolute, the conditioned and the Unconditioned, form and emptiness. In each of us and in all things, these two sides co-exist. And in Awakening they crash together, revealing that they are both and they are neither. Then “road” and “Nirvana” also crash together and fall apart. It’s like that old saying about peace: “There is no way to peace. Peace is the way.” Kempo and Ummon have both rolled up the road and swallowed it whole, and there is no road left to know.

There’s another koan, this one in the Blue Cliff Record, which looks at the same theme as this one: One day Changsha went for a walk in the mountains. When he returned to the gate of the monastery—that’s important, the monastery being the “negation” side to the “affirmation” side of worldly activity—the head monk said, “Master, where have you been?” Changsha said, “I’ve come from walking in the hills.” The head monk asked, “Where did you go?” Changsha said, “First I went pursuing the fragrant grasses, then I returned following the falling flowers.” The head monk said, “You are full of the spring, aren’t you?” Changsha said, “It even surpasses the autumn dew dripping on the lotuses.”

The seasons reveal the same dynamic of holding and letting go in the form of the potential and the manifest. Winter is the withdrawing, the sap returning to the roots of the trees, everything covered in snow, silence. In the daily cycles of day and night—visible and invisible—we see the same repeating flux. Changsha is contrasting spring with autumn, and if “spring” represents nature emerging in a profusion of colors, sounds, and smells, what is he really pointing to as the “autumn” mode of practice? And why would he declare the one better than the other? This poem by the American poet Wallace Stevens might serve as a Zen answer: “After the final no, there comes a yes. On that yes, the future of our world depends.” In the most profound sense, without yes, without the affirmative side of things, there would be no world at all. There is no coin without both heads and tails.

And now, Mumon’s verse:

Before taking a step, you’ve already arrived.

Before the tongue has moved, the teaching is finished.

Though each move is ahead of the next,

know there is still another way up.

Where is there to go? Where could we go, when there’s only this? What is there to say? What is there to teach when each one of us has been endowed with all wisdom from the beginning—from the no-beginning of time? “Though each move is ahead of the next”—progressing on the Path, evolving, maybe advancing through different koans—“know there is still another way up.” What’s the other side of both progressing and regressing? / / /

By Roshi Bodhin Kjolhede