A brief biography, description of the training at Bukkokuji Temple, and personal memories of Harada Tangen Roshi (Zen Master) by Roshi Bodhin Kjolhede

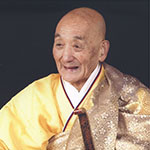

There is probably no more potent fuel for spiritual aspiration than an awareness of the inexorable law of transience. Tangen Roshi’s early life was marked by loss and unusual suffering. His mother, after being warned by doctors that bringing her pregnancy to term could prove fatal, did die while he was still an infant. For the rest of his life he felt a deep indebtedness to her, and a love that later evolved into a special affinity for the bodhisattva Kannon.

From childhood on, Tangen Roshi later said, he was “always very rebellious—as though in search of something”—and by age 12 his search began in earnest. A deep questioning arose in him as to the essential nature of things: “There is something I feel but don’t understand. I can sense its presence, but can’t grasp it.”

His feeling of separation from people and things, though not unusual in adolescence, seems to have been especially acute. But then, at age 18, he had a glimpse of that which is beyond suffering. During a school vacation, he climbed a small mountain alone. On the way up, consumed by self-reproach, he found himself chanting the rules of an acclaimed preparatory school which, he later surmised, brought his mind to a purified state. Once atop the mountain, the strong wind seemed to sweep away his feelings of worthlessness. Looking out over the Pacific Ocean, he felt himself expanding into an oceanic feeling of oneness with everything around him. It was a life-altering experience that left him feeling held, and protected, by a benevolent universe. It would prove instrumental in enabling him to survive the suffering yet to come.

When he turned 20, toward the end of World War II, Tangen joined the Japanese Air Force in China and volunteered to be a kamikaze (suicide) pilot. After a year of intensive training, he was assigned to his first—and final—flight. Just as he was about to board his plane, after the ritual cup of sake, he heard Emperor Hirohito’s voice on a loudspeaker, announcing Japan’s surrender. Overwhelmed by the timing of this turnabout, he vowed to dedicate his life to the service of others.

Circumstances still impeded him, however. In the aftermath of the war, he was captured by the Russians and held in a POW camp in conditions of severe hardship. Then Kannon again seemed to intervene. According to one source, a Russian officer forced him at gunpoint to sit down and drink vodka with him. Tangen ended up drinking so much that he had to be hospitalized, and it was just then that the others in his group were sent to Siberia, never to return.

When Tangen returned to Japan, in 1946, he was in a state of mental distress and soul-searching. A friend suggested zazen, which led him to attend some sesshins at a nunnery. The abbess, a disciple of Harada Sogaku Roshi, then pointed him to the latter’s monastery, Hosshinji (founded 1521). The spartan training at Hosshinji proved to be a perfect fit for the young Tangen, and in Harada Roshi he found the teacher to whom he would remain forever devoted (and who would become his adoptive father). Harada Roshi’s teaching galvanized and harnessed the spiritual longing that had built up over his short life of loss and suffering.

It has been said, “Anxiety is like a match—light it and it will show you the way out.” At Hosshinji, Tangen’s angst drove him to sit like a house on fire. For his first three years there, he wouldn’t lie down to sleep, instead doing zazen through the night. He would sometimes sit in a bamboo grove on the mountain behind the monastery, gripping one of the trunks and roaring, “MU! MU! MU!” He once became so exasperated that he punched himself in the face, dislocating his jaw. Later he would surely have realized the absurdity of punishing himself.

Through his long-sustained exertions he had lost much weight and grown increasingly weak. But one of the wondrous effects of wholehearted zazen is its self-correcting power, and like Siddhartha after his own period of fanatical asceticism, he finally found a greater balance in his efforts, and subsequently came to his first kensho.

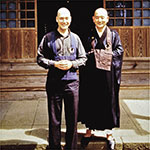

At age 29, Tangen was the head monk at Hosshinji when Philip Kapleau first walked through the monastery gates in 1953. Kapleau’s studies in Zen philosophy under D.T. Suzuki in New York had convinced him of the Zen saying, “A picture of a cake doesn’t satisfy hunger,” even as it left him brimming with concepts about Zen. But by now Tangen had developed the insight to see through Kapleau-san’s intellectual pride and brashness, recognizing beneath it the same anguished searching of his own youth. Their countries had been mortal enemies, leaving them both scarred and dedicated to realizing that which united them: their innately enlightened nature.

Tangen also must have seen that Kapleau-san, his senior by 12 years, had the full package: the compelling need to come to realization, and the determination to do so. His demands on Kapleau-san matched his faith in him. Once when the American newcomer was sitting in the dokusan line, Tangen, who alone at the monastery had learned a little English, was sitting behind him ready to go in with him as his interpreter. No sooner had Kapleau-san struck the bell and stood up than Tangen, without warning, struck him violently behind the ear. Kapleau-san, enraged, took a swing at him, but with no time to lose, stormed straight in to see Harada Roshi. For the first time, Kapleau-san was able, in his aroused state, to respond to the Roshi no-mindedly, from the guts rather than the head. Harada Roshi signaled his delight. From then on, Kapleau writes in Zen: Merging of East and West, he found himself “operating on a higher energy level, and at dokusan was no longer afraid of the roshi.” Tangen had known well that compassion can take the form of harshness.

He also meted out his special compassion for the American even when doing so cost him precious sleep. On the last night of a seven-day sesshin, after the formal schedule had ended for the day, Kapleau-san secluded himself in the bathhouse to continue his sitting. Tangen, ever solicitous of his struggling foreign charge, followed him in and spent hours urging him on with the kyosaku (encouragement stick). By the end of the night, they had bonded to a degree unique to such shared exertions. As dawn broke, they silently embraced, and Kapleau remained even further indebted to his mentor, friend, and Dharma-brother.

In 1955 Harada Roshi sanctioned Tangen as a teacher, and sent him to the dilapidated old temple of Bukkokuji (founded 1502), half a mile from Hosshinji, to begin teaching. Just 31 years old then, Tangen spent his days rebuilding and repairing the temple, conducting ceremonies, and going on takuhatsu (mendicancy) to raise money before sitting in zazen into the night.

Although Bukkokuji was not a fully certified training temple, Tangen Roshi’s reputation as a teacher and example of compassion and wisdom gradually spread internationally by word of mouth. By the mid-90s as many as 60 participants from around the world were crowding into his sesshins. Eventually he was offered a senior position at Eiheiji, one of the two mother-temples of the Japanese Soto Zen school, but he politely declined. Not long afterward, he suffered a heart attack, but after recovering he resumed teaching. Later he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, which finally brought his teaching career to a halt.

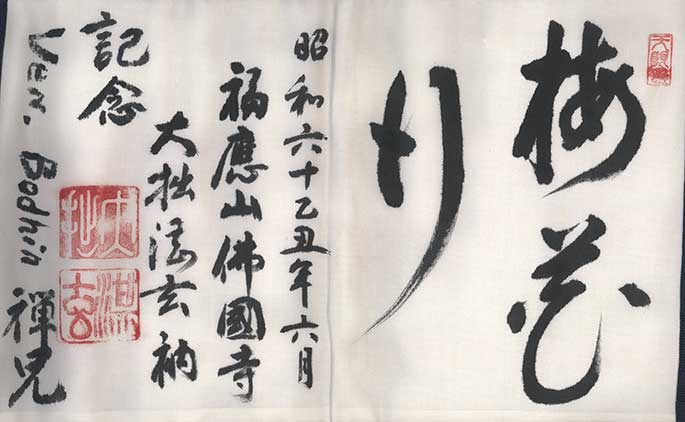

No biographical profile of a Zen teacher would be complete without some description of the training at the temple, which always reflects the teacher’s understanding and practical application of the Dharma. In March, 1985, I arrived at Bukkokuji for three months of Zen training (with another three months at Sogenji later in the year). The challenge I faced is known to anyone with involvement at one Zen center upon entering a temple with a different teacher: adapting to differences in procedures, policies, and other forms. The challenge is especially difficult in Japan, where these prescribed norms are typically not explained to new residents; the newcomer is expected to learn them simply by joining with the others in the daily rounds and always keeping eyes and ears open. The key value is to adapt and harmonize with the group, as enshrined in the Japanese warning: “The nail that sticks up gets pounded down.”

Bukkokuji was one of the few residential training temples in Japan that accepted gaijin (foreigners), most of whom arrived there seemingly as ignorant of Japanese Zen monastic rules as of Japanese culture generally. Tangen Roshi was willing to go the extra distance to give even those with no Zen experience a shot.

After 14 years of residential training under a teacher with long training himself in Japan, I landed at Bukkokuji with an introduction to Japanese Zen culture. But like most of the gaijin there, I neither understood nor spoke any Japanese. There was a young American woman who knew enough Japanese to sometimes interpret for Tangen Roshi in dokusan, but with respect to what else was happening at the temple, even she often left us fellow gaijin in the dark. Soon after arriving there, I happened to see her, across the central courtyard, heading to the Buddha Hall in a special robe. “Belenda, what’s going on?” I called out. “Oh, we’re celebrating the Buddha’s Birthday”—in Rochester one of the two biggest weekends of the year. The next month they had Jukai (the ceremony of receiving the Buddhist precepts), but I only heard about it some 20 minutes into the ceremony. To be sure, both of these events were tiny-scale there, but Jukai is considered the most significant of all Buddhist ceremonies other than ordination. Leaving the gaijin to fend for themselves for information may have been a feature of Tangen Roshi’s teaching. “Never explain” is a key Japanese Zen directive that in Rochester Roshi Kapleau himself often cited (while nonetheless providing plenty of printed rules and guidelines—an accommodation to Western needs).

The relatively laissez-faire tone at Bukkokuji was difficult for this Kapleau disciple to adjust to. We were assigned only 1½ hours of work a day, with Tangen Roshi urging us to “just take your time—no rush.” Seldom was any instruction given in how to do the job, and it was usually not clear who one’s supervisor was, or even if there were any at all. There were tea breaks, lasting as long as 45 minutes, every morning and evening, and we were expected to stop talking (which was scant anyway) when the roshi was present. Most of the day between the morning and evening sittings was unstructured. It was not uncommon for lay students (non-residents) to come late to sittings. Most residents belted the dokusan bell hard, evidently without correction. Tangen Roshi never ended dokusan until everyone had had the chance to get in, which sometimes cut into meals, leaving residents waiting for him at the table to begin. And since the dokusan room had no doors, anyone walking by could have looked in to see what was happening there.

At Bukkokuji sesshins the kyosaku was used noticeably less than it was in Rochester at the time, and drastically less compared to Rochester sesshins in the 1970s. Accounts in The Three Pillars of Zen suggest that the stick may have been heaviest of all when Kapleau-san was at Hosshinji—when Tangen-san was the head monk. When I marveled at this change in stick culture from that of Tangen-san of the 1950s to Tangen Roshi of 1985, Rochester Sangha member Wes Borden, who was with me at Bukkokuji at the time, recounted how he had asked Tangen Roshi about this while there on a previous visit. In reply, Tangen Roshi, speaking through interpreter and fellow RZC member Kenneth Kraft, explained: “When Harada Roshi died, the training at Hosshinji fell apart. I realized that it was because the discipline was all from the outside. So now I think the discipline should come from the inside. I used to hit the monks terrifically hard with the kyosaku, but now I hit like a baby.”

I took this story to heart, and after succeeding Roshi Kapleau in Rochester the following year had our sesshin monitors dial down the use of the kyosaku to what it has been ever since. Tangen Roshi’s belief in nurturing discipline “from the inside” would also explain the largely unstructured daily schedule at Bukkokuji. Having a “wide pasture” of free time at our disposal imposed on us the decision of how to use that time. In a sense, it demands more of each individual.

If the atmosphere at Bukkokuji was generally looser than at many Zen centers I’d been to, in some ways it was stricter. Obedience to Tangen Roshi was non-negotiable. No one was permitted to go outside the walls of the temple without his explicit permission. There were no days off from the schedule of morning and evening sittings, with wake-up always at 3:45 am. The three meals each day were mainly rice. Before going out on takuhatsu we had to submit to his meticulous inspection of our attire—after all, we were representing the Dharma to the public—and he once adjusted my undershirt at the throat to make an exposed quarter-inch of it disappear. Belenda recounted that he had been “furious” with her for shaving her head without his permission (“He says that I should look like a woman”).

Shortly after I had settled in at Bukkokuji, we were all roused from bed at midnight by the roshi’s lilting cries through the courtyard: “Accident…!” “Fire…!” “Accident…!” “Fire…!” Unbeknownst to us, this was his way of memorializing an act of arson committed on that night two years earlier, when a mentally disturbed resident set a fire in the zendo building. Alarmed, we streamed out of our rooms to fight the blaze in a hastily-formed bucket brigade, with Tangen Roshi spurring us on excitedly, only to find ourselves heaving water onto the cold cement pyramid of memorial tablets in the graveyard. After some 15 minutes of this he had us change clothes and sit in the zendo for a short talk by him. Then we repaired to the dining room for rice balls and special tea while he regaled us with hearty reminiscences of details of the actual fire.

At a tea break one day, Tangen Roshi told us of a woman who had just joyfully informed him that her husband, who had needed surgery for stomach cancer eight months earlier, was just pronounced cured. When the wife had first learned of his diagnosis, Tangen Roshi said, she came to him overwrought with concern. “What do you think I told her?” he asked us, beaming. Someone guessed, “Kannondo (Kannon Room).” “That was the second thing I told her,” he grinned. “What was the first thing?” Finally, he told us: “Surrender.”

At the morning tea break on my first day at Bukkokuji, Tangen Roshi passed around maple sugar candies that I had brought him from Rochester. This reminded him, he said, of the deep karma he felt with a maple tree that had saved his life right after taking charge of Bukkokuji. While hiking on the mountain behind the temple, he had slipped and fallen over a precipice. About thirty feet down he was caught in his midsection by the single branch left on the tree, which left him with permanent pain in his hip. But it saved him from almost certain death. While falling, he said, he realized “ego… unnecessary….” Then he brought out the branch itself, which someone, to his regret, had cut off to present to him.

It is hardly surprising, given Tangen Roshi’s three narrow escapes from death, that his faith in the grace of Kannon was unwavering. Whereas the Buddha’s Birthday and Jukai were both minor observances, the Kannon Day Ceremony, held every month, lasted 2½ hours. Beyond that, in his own person he proved himself, every day from before dawn until after dusk, the flowing embodiment of compassion. Just as Kannon figures are sometimes shown with many heads and arms, he seemed to notice everything about his students and respond to them according to their needs, whether sternly or tenderly.

When taking leave of Tangen Roshi and Bukkokuji on the day after a seven-day sesshin, Wes and I were mortified to see Tangen Roshi wake all the residents from their deep, hard-earned naps to see us off at the temple gate. Later I came to see this gesture as not just Japanese etiquette, but a tribute to us that signaled the same faith he had in everyone—“all buddhas, bodhisattva-mahasattvas.” No doubt he hoped that it would leave us determined to live up to his respect. That morning, over tea with us, he said, “Zen is dying in Japan and being reborn in America.” His life of exertion has done much to keep the flame of the Dharma alive in both East and West. / / /