A Veteran Chair-sitter Shares What He’s Learned Through Many Years of Zen Practice

Sooner or later in a lifetime of Zen practice, many of us find it helpful, if not necessary, to “sit” (meditate) in a chair. The need could be temporary—wanting to sit up late in sesshin far into the night, with the body calling out for postural variety. Or, while traveling without cushions, a chair can almost always be found, so how to use it? An injury (broken toe, sprained ankle, inflamed knee, etc.) could temporarily leave you with chair-sitting as the only way to maintain daily zazen. And for some, even from the start, any number of other physical constraints may make sitting in a chair a more or less permanent necessity.

Chair-sitting can be (at first) difficult and demanding, while still being powerful and effective. If you are going to sit in a chair, tell yourself right from the start that it will be your own seat -— of practice and awakening. Know that you are not making a compromise; true nature is not any more present or accessible on a mat with a cushion than it is on a chair.

There are certain “knacks” involved in chair-sitting, just as there are for the cross-legged kind—little details, that, when observed and repeated, will make it easier to get centered and energetically quiet.

Ready. The Essentials of a Solid “Seat.”

By reviewing the psycho-physical reasons why the lotus posture is ideal (for those who can maintain it without twitching and squirming) for zazen, we can get a window into the essentials that comprise a solid “seat” in a chair. I recall Roshi Kjolhede explaining in a teisho some time ago that the lotus posture is not recommended just (or even primarily) for aesthetic reasons (although there is real beauty in the balanced symmetry of a seasoned practitioner sitting cross-legged on the mat). Rather, the posture was implemented by sages millennia ago (predating even the time of Shakyamuni Buddha) because it optimally provides for stable alertness and for open centeredness. The lotus posture endows the sitter with:

- A broad, stable foundation

- Ideal support for an upright spine, encouraging its natural curvature

- The drawing together of all four limbs at the body’s center (the hara region)

- A perfect arrangement of the body parts for effortless breathing

Any sort of seated zazen uncovers at least two essential elements of our being: a deep, dynamic stillness, and a simple awareness. One settles into these qualities more quickly and effortlessly if a correct posture is consistently maintained. The limpid, awake, quiescent aspect of our nature won’t come to the foreground if we’re constantly moving and twitching during a round, so an ideal sitting posture is one that will maximize the stability of the entire frame.

An upright and stable posture will, of itself, generate substantial energy over time; an open posture allows energy to flow; and a centered posture permits more energy to course through the system without generating restlessness or agitation.

Get Set. Preparing to Chair Sit.

So, let’s examine in detail how to maximize these postural qualities of an upright and stable, centered openness—in a chair.

1. Experiment

First, recognize that these are general guidelines – if your particular physical situation does not permit exact adherence to them, make some adjustments, or work out something similar that makes sitting manageable for your condition. Experiment! Ask for help and guidance from teachers, experienced sitters, your yoga teacher, your physical therapist… and keep trying. (For more ideas on developing a strong posture in a chair, see Esther Gokhale’s 8 Steps to a Pain-Free Back, especially the chapter on “Stack Sitting”, pp. 68-93).

2. Your Chair

The chair you use should be solidly built—not wobbly. The seat should be firm or firmly padded. Depending on the chair’s height, and on the length of your shin bones, you may want to place one or more cushions on the seat.

3. Solid Points of Contact

The solid, triangular base provided by the lotus posture can be approximated in a chair by having three solid points of contact: the “sitz bones” (ischial tuberosities) and the two feet. If your legs are short, find a chair with a seat low enough to the ground to allow your feet firmly to rest on the floor. Folks with very short shin bones who can’t find an appropriately-sized chair may need to place a flat cushion or mat, or something similar, on the floor, to allow their feet to be grounded firmly.

4. Cushion Arrangement

Your cushions should be placed toward the front of the chair seat, as you won’t be using the chair back at all (I’m unfamiliar with serious back problems, and so cannot offer much advice here to those who find it necessary to support their back with cushions, or to lean back in the chair). Arrange your cushions so they are slightly more elevated at the rear of the seat: put the flat cushion under the back end only of the round cushion, or place a “wedge” cushion under a rectangular support. Again, experiment.

5. Chair Position

To avoid eye strain and make it easier to keep the eyes open, don’t place the chair too close or too far from the wall – your face should be about as far from the wall or divider as it would be for someone sitting on a mat.

Make sure your chair is precisely square to the wall, so that a line between the two front or the two back legs would be parallel to the wall – doing this will help get your body facing the wall squarely. If your pelvis is aligned even slightly at an angle to the wall, there will be an unconscious effort to twist the upper body back to square, rotating it on the pelvis, and this can induce back strain.

Walk around to the front of the chair, set your feet about shoulder width apart, and look down to check if the great toe of each foot is equidistant from the wall (again, to set up squarely). Hinge the torso forward at the hips, thrusting the buttocks out behind, and lower them to your cushion. If you don’t quite feel like you’re right on top of your “sitz bones” (ischial tuberosities), do what folks sitting on a mat often do: really hinge the upper body forward all the way at the hips, thrusting the buttocks way out behind, then feeling the “sitz bones,” find and maintain contact with the cushion while looking up; then follow the nose up, slowly bringing the torso to vertical.

6. Your Feet and Thighs

Each entire foot should feel planted flat on the floor (or supporting mat), with contacts at the heel, the ball, and the lateral pad of the forefoot. Experiment with whether you feel more stable and powerful having the feet point straight ahead, or with the toes swung out at an angle. Don’t let the kneecaps protrude out beyond the toes below them. Check on whether you feel better with the knees and feet close together or fairly wide apart. If your legs and feet are placed just right, you should feel poised, like you could easily stand right up without having to lean forward more than just a bit.

If your mid-back gets tired quickly, experiment with a little more, or a little less, elevation: you want the tops of your thighs to be slanting down, at least slightly, toward the knees. Having the centers of the hip joints higher than the tops of the knee joints opens up the hara region, allowing for an easier settling of energy in to this vital center; it also modestly anteverts (tilts forward) the pelvis, which, in turn, effortlessly supports the natural curvature of the spine.

7. Your Hands, Shoulders, and Neck

Next, place your hands in your lap, in the zazen mudra (sometimes called the cosmic mudra, with the back of the left hand resting in the palm of the right, the thumbs slightly touching). Alternatively, lightly clasp and hold one hand with the other. To avoid strain in the shoulder area, the weight of your hands should be well-supported while resting in the lap; if your arms are too short to allow this to happen naturally, arrange a little cushion or rolled-up hand towel under the back of your hands (there is a veteran member of the Zen Center who uses a U-shaped “neck pillow” from an airport gift shop for this purpose).

Take a moderately deep breath, hold it for a second, and roll one shoulder up and back, and then roll the other shoulder. Exhale normally, and feel the arms hanging naturally off at the sides. Becoming aware of the soft palate area at the back of the roof of your mouth, allow it to float straight up a little; or, tuck the chin in slightly and feel the back of the neck grow long and tall—either way will get your head properly aligned with the neck, all hovering over the center of the torso.

Go. Doing Zazen in a Chair.

With this solid base in place and remaining aware of the sitz bones under you, swing the upper body off to the left in a fairly wide arc, and then to the right, and let the upper body swing back and forth in arcs of ever-decreasing amplitude until the torso comes to rest naturally and quietly in the center. If it feels necessary, roll each shoulder up and back again a little, and check that the chin is still slightly tucked in. Lower the gaze down the wall a bit, de-focus the eyes, and you are all set for a good round of sitting!

As with sitting in any manner, you’ll become aware of your body’s posture from time to time during a round, and if you sense it’s become misaligned, make the subtle shifts necessary. But apply such adjustments conservatively: you may eventually find, by staying still, that you just weren’t accustomed to being in such a naturally good form before; it might have just felt strange at first. When in doubt, don’t move.

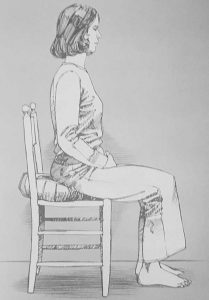

If you’re lucky enough to sit with a group that has experienced monitoring, ask those folks to check your posture from time to time and to straighten you up if they find you “listing to starboard” or “tilting out over bow.” Or, have a friend snap a photo of you from the side and the back after you’ve settled into a round of sitting – then compare your posture to the ideals shown on this web site or in the Appendix at the back of The Three Pillars of Zen.

Bring a strong sense of bodily intention to your chair, determined that you will lean in to your practice right there on that seat, throughout each round. Perhaps at the start of a block of sitting, take a moment to imagine yourself as a grand mountain, with deep roots, and towering all the way through the clouds, or, as an accomplished equestrian sitting tall on a strong, eager horse, ready to bound off in any direction.

~ Larry McSpadden

Sooner or later in a lifetime of Zen practice, many of us find it helpful, if not necessary, to “sit” (meditate) in a chair. The need could be temporary—wanting to sit up late in

Sooner or later in a lifetime of Zen practice, many of us find it helpful, if not necessary, to “sit” (meditate) in a chair. The need could be temporary—wanting to sit up late in